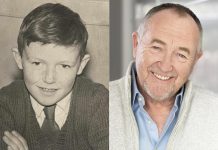

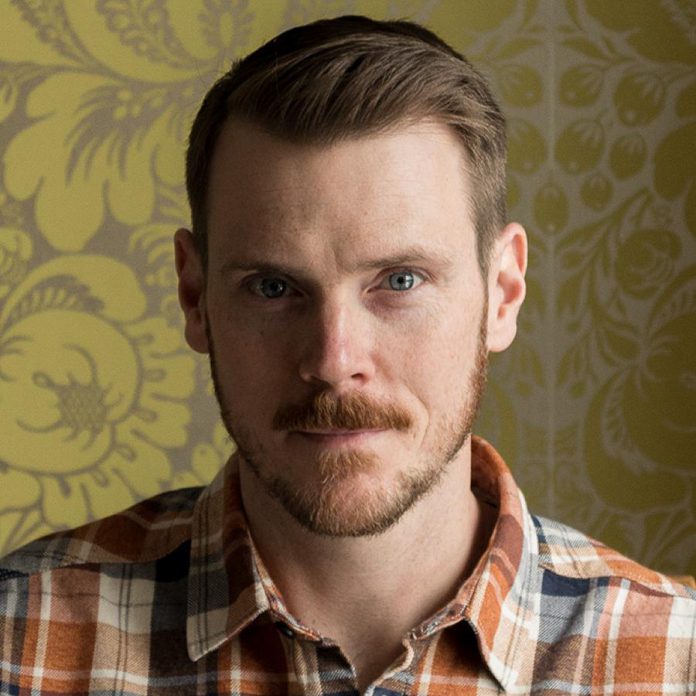

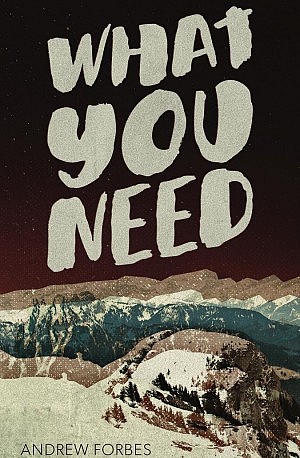

Andrew Forbes has written film and music criticism, liner notes, sports columns, and short fiction. What You Need is his debut collection of fiction.

Andrew’s work has been nominated for the Journey Prize and has appeared in The Feathertale Review, Found Press, PRISM International, The New Quarterly, Scrivener Creative Review, The Journey Prize Stories 25, This Magazine, Hobart, The Puritan, All Lit Up, The Classical, and Vice Sports.

Andrew was born in Ottawa, where he attended Carleton University. He lives in Peterborough.

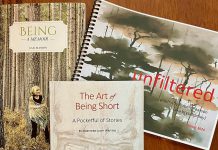

What You Need is available at Chapters Indigo, Amazon, and the independent literature retailer All Lit Up. The Peterborough book launch for What You Need takes place at Gallery in the Attic (140 1/2 Hunter St. W., Peterborough) on Friday, April 24th from 7 to 9 p.m., and will include readings from the book by Andrew and fellow writers Angela Hibbs and Janette Platana.

An excerpt from “Dorothy” from What You Need by Andrew Forbes (Invisible Publishing, 2015)

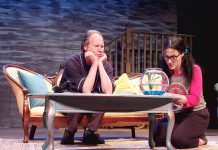

She’s two-and-a-half years old, and she is something. I know it’s my parental duty to say such things, and I know your place is to smile approvingly, then roll your eyes and shake your head once I look the other way. But you need to trust me on this: she really is amazing.

She asks me to sing her the alphabet song, and I’ll do it but stop periodically at different spots, and she will, without hesitation, fill in the next letter. Two years old.

I hum the theme to Sesame Street to her and she breaks into song, getting most of the words right. Those she forgets she’ll simply leave out, or she’ll look at me with a great big open expression on her face, asking me to fill them in.

I know you’re expecting a work of fiction. My name is Andrew Forbes and I am a writer and a stay-at-home dad. I write short stories. Almost everything I write is fictional, but please trust me on this: this is a true story.

Dorothy, my wife Marie, and I live in Peterborough, Ontario. Marie writes policy concerning wildlife for the provincial government. Dorothy and I keep a very full schedule of playgroups, story circles at the library, gymnastics for toddlers, swimming lessons, and assorted errands. Our days are packed.

The girl loves animals, especially cats and dogs. We have an unruly blue heeler named Rebus and an odd-eyed white cat named Rudy. Dorothy laughs hysterically when the pets do the slightest thing, and nearly hyperventilates when the dog chases the cat. It’s an unhinged, full-body laugh that we try to replicate with antics and tickling, but it never reaches the frenzied pitch it does when animals are involved.

And then there’s this: Dorothy can walk up the wall and across the ceiling.

This is true.

She’ll be standing on the wall so that she is sideways and you’re straight up and down, and if she’s holding a toy she’ll drop it and it will fall hard onto our blonde hardwood floors. She began doing this just before her second birthday, though she’d been walking on the horizontal plane since she was eleven months old.

We were in the family room, surrounded by toys. Marie was in the kitchen making herself a cup of tea. I think it was a Saturday morning. Dorothy lay on her side, pressed her feet to the wall just above the baseboards, and began walking. Soon she was halfway up the wall, giggling a bit. To Marie I said, “Look at this.” Marie looked, slowly put down her mug, and walked toward us. “Be careful, Dot,” she said.

“This is strange, right?”

“Well, yes,” said Marie, but even without her saying so I could tell that she felt as I was: that all parents suspect their children to be exceptional, but here was our proof.

In a minute Dorothy had had enough, and simply walked back down to the floor.

“How did you do that, Dottie?” I asked.

“Oh, dad, it’s okay,” she said.

“Dorothy,” I said, “what’s happening?”

“Daddy,” she said, “I want a juice box.” We still call them juice boxes, even though most of them are now little foil pouches.

THERE IS A PHOTOGRAPH which shows Marie and me at Navy Pier in Chicago. Marie is six months pregnant, her face soft and cherubic. We are in Chicago as a grand kiss-off to our pre-parental life. Over an extended weekend we have seen the Cubs lose to Milwaukee, strolled the halls of the Art Institute, taken the El, roamed around the loop, and seen the dolphin show at the aquarium. Now it is Sunday evening, the night before we are to fly home, and we are on Navy Pier, a questioning finger stuck outward into Lake Michigan, taking in the sights before retiring to a dark restaurant for deep dish pizza. The sun is sinking behind the skyline, and we are pausing for a photo, the camera in my hand at the end of my outstretched arm, pointed back at us. Her arms are around my waist, my left arm is over her shoulders. In the photo the lake appears as an indistinct bluish haze. There is a lighthouse tower at the end of the pier, just visible over Marie’s shoulder. We are smiling, happy. And as I look at this photo now, it seems to me, with the wisdom bestowed by the intervening years, that if we resemble anything it is those seamen awaiting commencement of an atomic test at Bikini Atoll. We have been told time and again, by countless experts, some of what we might expect, but if we listened at all we did so blithely, casually, unable to absorb the enormity of it. But soon the thing will come, and it will be huge. And we are destined to live with its effects — the shockwaves and the lingering consequences. There will be no way to imagine our lives as they were before the event.